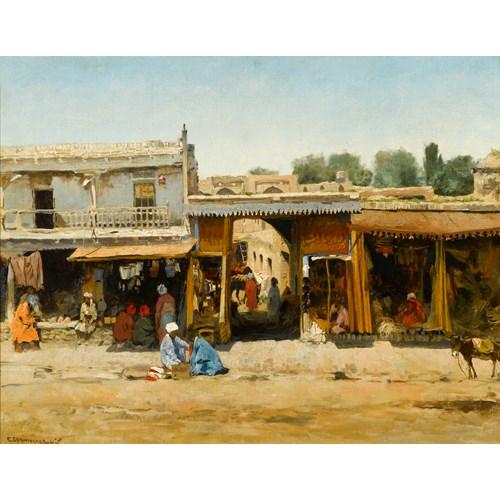

Marketplace

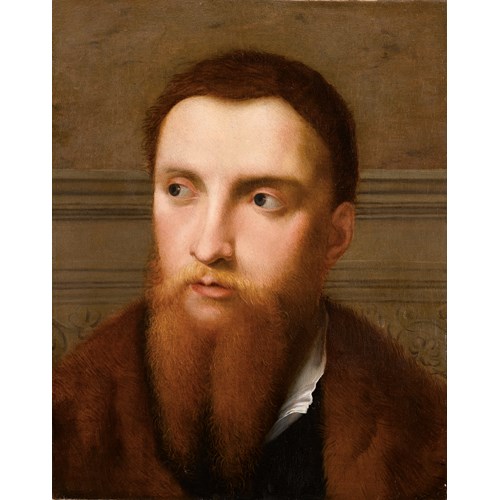

Lucretia

‘Taking a knife which she had concealed beneath her dress, she plunged it into her heart, and sinking forward upon the wound, died as she fell.’

- Livy Ab Urbe Condita I.58

This arresting full-length portrait of Lucretia, the epitome of virtue and chastity, is memorable not only for the carefully depicted pose but also the strikingly opulent surroundings in which she has been placed. Seated in the foreground against an elaborately draped green, velvet canopy, Lucretia balances tentatively on the edge of what is, presumably, her marital bed and the scene of her violent assault at the hands of Tarquinius. Her hand rests awkwardly upon an intricately carved wooden figure atop a fluted Ionic column. The combination of this strange nude statuette and the luxuriousness of the crimson damask at the foot of the bed with the golden tassel of a cushion, lends an otherwise tragic scene a peculiarly charged air of sensuality.

The story of Lucretia’s fate was integral to the history of Rome’s foundation and became a powerful moral fable in the Roman psyche. Retold in Livy’s Histories, it provided countless opportunities for artists, poets and musicians from the Renaissance onwards to exploit its dramatic and didactic potential. According to Roman mythology, Lucretia’s rape by the unscrupulous son of the last king of Rome, Sextus Tarquinius, was the cause of the overthrow of the Roman monarchy and the consequent birth of the Roman Republic.

Lucretia was married to Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus and her father was Spurius Lucretius Tricipintinus. Livy tells us that in 509BC, the violent Tarquinius desiring to violate the legendary chastity and moral rectitude for which Lucretia was famed, planned to rape her. Telling her that if she refused to acquiesce to his demands he would kill her and place her body next to that of a slave, she tearfully complied with whatever he forced her to do. That she would be accused of committing adultery with a lowly slave engendered far greater shame than anything, however terrible, Tarquinius would have her do.

Once Tarquinius had left, she summoned her father and husband to her and when they arrived she told them of Tarquinius’ evil actions. Despite their reassurances and attempts to comfort her distress, Lucretia made them promise to avenge her violation. Feeling that this would not be enough, however, she took a sword and plunged it into her heart, uttering to them the words which secured her reputation as the archetypal Roman matrona: ‘It is for you to determine what is due to him, for my own part, though I acquit myself of the sin, I do not absolve myself from punishment; nor in time to come shall ever unchaste woman live through the example of Lucretia.’¹

Attributed to Georg Pencz, Lucretia recalls a number of strikingly similar female nudes by Pencz. A depiction of a sleeping woman, based heavily on the Venetian artists whom he so admired, notably Giorgione (c.1477-1510), resembles Lucretia in terms of form. The exact and realistic draughtsmanship of the sleeping woman is typically northern European, as are the still life elements that can be seen beyond in a niche in the background. The same elements and meticulous attention to detail are to be found in the bed post upon which Lucretia’s hand rests, as well as in the highly realistic imitation of fabrics and marble inlay.

The subject of Lucretia’s suicide is also treated by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), as well as by Pencz’s master, and Cranach’s contemporary, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), and both artists’ respective interpretations of the subject shed a great deal of light on the present rendition of Lucretia. Cranach the Elder was preoccupied by Lucretia throughout his lifetime with more than thirty-five other compositions attributed to him and his circle. In a number of his extant compositions, Lucretia is shown either full-length or half-length and partially clothed or entirely nude apart from a beautifully delicate veil that coils sinuously around her body. The present work alludes to such presentation with a flimsy, transparent wisp of gauze provocatively encircling Lucretia’s waist. In Cranach’s conception of the story, as in his 1533 version in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin, the rape itself is never depicted, as in this present composition. Rather, it is the abject figure of Lucretia preparing to take her own life, in order to salvage her honour and dignity, that captures both artists’ attention. Given the subject matter, it is remarkable too, just how devoid of violence Cranach’s Lucretias tend to be. At most, as in Dürer’s ominous version, there will be a discreet stream of blood drawn by the superficial piercing of the sword. Yet, there is not even a hint of violence in this painting attributed to Pencz. The surreal atmosphere seems wholly at odds with the tragic end that befalls Lucretia. Dürer, despite the heavily criticised composition of his Lucretia, does manage to imbue the work with an atmosphere of great solemnity and foreboding that seems to be curiously absent in both Cranach’s version and the present work.

It is likely that Cranach viewed Lucretia as he did the other heroines whom he frequently depicted such as Judith, the Old Testament heroine, and Salome, the wife of King Herod: as an iconic figure and the embodiment of virtue rather than one based in historical myth, or indeed reality. This is perhaps in no small part due to the erotic nature of Cranach’s nudes and this idea can certainly be transposed onto the present Lucretia.

Whilst not as flamboyantly dressed as some of Cranach’s versions, the present work shows a woman surrounded by luxury and dripping with ornate and precious jewellery. The intricate detailing of her pendant and bracelets bear a distinctly Northern European flavour and have far more in common with versions by Cranach. Arguably, the artist’s decision to clothe his subject in little else but jewellery reveals a startling contradiction: on the one hand, she historically embodies the wifely virtues that Lucretia herself exemplified, while in the other, she is presented to us in a suggestive pose. It is highly similar in this respect to Pencz’s female nude previously discussed. Such playful eroticism is entirely missing from Dürer’s 1518 version. Interestingly, however, the backdrop of Lucretia’s bedroom, which is not included by Cranach, is borrowed in the present work from Dürer’s careful intimation of drapery.

Pencz himself evidently derived much inspiration from the story as he painted at least one other version of Lucretia on the point of suicide. In addition, as part of a selection of engravings from Roman history, Pencz includes the scene when Tarquinius surprises the sleeping Lucretia, threatening her with his sword if she makes a single noise. The stylistic similarities between the present work and Pencz’s engravings are exemplified in his rendition of the story of Paris and Oenone from 1539. The voluptuous figure of Oenone and the luxurious drapery that conceals very little are strongly reminiscent of the figure of Lucretia. The facial expressions of the two women are highly similar even though Oenone is composed in profile.

Pencz was a German draughtsman and painter who was active in the workshop of Dürer. He arrived in Nuremberg in 1523 and subsequently entered Dürer’s workshop. Imprisoned, together with the Beham brothers, for allegedly disseminating the radical political and religious views of Thomas Müntzer, he was eventually pardoned and free to carry on with his painting. Heavily influenced by his master, Pencz’s prints of the 1520s include copies after prints by Dürer, employing the fashionable northern Italian style. Pencz was probably in northern Italy and Venice in the late 1520s and returned to Nuremberg in c.1529. Works by Venetian artists exerted a great deal of influence upon him. Similarly, a painting of Judith (Alte Pinakothek, Munich) shows a half-length figure inthe manner of the early work of Palma Vecchio (?1479/80-1528) or Titian (c.1485/90-1576).

In the years following 1533, Pencz made several large ceiling pictures on canvas and was one of the first in Germany to conceive of ceiling pictures as a continuous whole. He was commissioned by Hirschvogel to do a ceiling painting of the Fall of Phaethon (preparatory drawing, Nuremberg), for the main room of the Bolognese Renaissance-style house built in his pleasure grounds. Peter Flötner (1485/96-1546) provided the interior decoration, and Pencz’s painting was clearly influenced by the furnishing and decoration by Giulio Romano (?1419-1546) of the Palazzo del Te, Mantua, which he saw when he visited Italy in the late 1520s.

Pencz completed a prestigious commission from King Sigismund I of Poland to paint scenes from the Passion (1538) for the silver altarpiece in the Jagiellonian chapel in Wawel Cathedral, Kraków (in situ), unfinished after the death of the court painter Hans Dürer (1490-?1538).

Between 1539 and 1540, Pencz seemingly made a second journey to Italy, going as far as Rome. There are many indications of this in his surviving drawings and engraved prints from the period. A revisit to Mantua is indicated by the large engraving of the Capture of Carthage after Romano’s work of 1539. This second Italian journey also affected Pencz’s religious and mythological paintings, which mostly contain a few figures shown half-length in the Venetian style.

In September 1550 the Prussian Duke Albert sent for him to come to Königsberg as a court painter, at the instigation of the preacher Andreas Osiander, whose portrait Pencz had painted in 1544. He set out but died en route.

We are grateful to Mr. Jan de Maere for the attribution of the work to Georg Pencz.

¹ Livy Ab Urbe Condita I.57-60.

- Livy Ab Urbe Condita I.58

This arresting full-length portrait of Lucretia, the epitome of virtue and chastity, is memorable not only for the carefully depicted pose but also the strikingly opulent surroundings in which she has been placed. Seated in the foreground against an elaborately draped green, velvet canopy, Lucretia balances tentatively on the edge of what is, presumably, her marital bed and the scene of her violent assault at the hands of Tarquinius. Her hand rests awkwardly upon an intricately carved wooden figure atop a fluted Ionic column. The combination of this strange nude statuette and the luxuriousness of the crimson damask at the foot of the bed with the golden tassel of a cushion, lends an otherwise tragic scene a peculiarly charged air of sensuality.

The story of Lucretia’s fate was integral to the history of Rome’s foundation and became a powerful moral fable in the Roman psyche. Retold in Livy’s Histories, it provided countless opportunities for artists, poets and musicians from the Renaissance onwards to exploit its dramatic and didactic potential. According to Roman mythology, Lucretia’s rape by the unscrupulous son of the last king of Rome, Sextus Tarquinius, was the cause of the overthrow of the Roman monarchy and the consequent birth of the Roman Republic.

Lucretia was married to Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus and her father was Spurius Lucretius Tricipintinus. Livy tells us that in 509BC, the violent Tarquinius desiring to violate the legendary chastity and moral rectitude for which Lucretia was famed, planned to rape her. Telling her that if she refused to acquiesce to his demands he would kill her and place her body next to that of a slave, she tearfully complied with whatever he forced her to do. That she would be accused of committing adultery with a lowly slave engendered far greater shame than anything, however terrible, Tarquinius would have her do.

Once Tarquinius had left, she summoned her father and husband to her and when they arrived she told them of Tarquinius’ evil actions. Despite their reassurances and attempts to comfort her distress, Lucretia made them promise to avenge her violation. Feeling that this would not be enough, however, she took a sword and plunged it into her heart, uttering to them the words which secured her reputation as the archetypal Roman matrona: ‘It is for you to determine what is due to him, for my own part, though I acquit myself of the sin, I do not absolve myself from punishment; nor in time to come shall ever unchaste woman live through the example of Lucretia.’¹

Attributed to Georg Pencz, Lucretia recalls a number of strikingly similar female nudes by Pencz. A depiction of a sleeping woman, based heavily on the Venetian artists whom he so admired, notably Giorgione (c.1477-1510), resembles Lucretia in terms of form. The exact and realistic draughtsmanship of the sleeping woman is typically northern European, as are the still life elements that can be seen beyond in a niche in the background. The same elements and meticulous attention to detail are to be found in the bed post upon which Lucretia’s hand rests, as well as in the highly realistic imitation of fabrics and marble inlay.

The subject of Lucretia’s suicide is also treated by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), as well as by Pencz’s master, and Cranach’s contemporary, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), and both artists’ respective interpretations of the subject shed a great deal of light on the present rendition of Lucretia. Cranach the Elder was preoccupied by Lucretia throughout his lifetime with more than thirty-five other compositions attributed to him and his circle. In a number of his extant compositions, Lucretia is shown either full-length or half-length and partially clothed or entirely nude apart from a beautifully delicate veil that coils sinuously around her body. The present work alludes to such presentation with a flimsy, transparent wisp of gauze provocatively encircling Lucretia’s waist. In Cranach’s conception of the story, as in his 1533 version in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin, the rape itself is never depicted, as in this present composition. Rather, it is the abject figure of Lucretia preparing to take her own life, in order to salvage her honour and dignity, that captures both artists’ attention. Given the subject matter, it is remarkable too, just how devoid of violence Cranach’s Lucretias tend to be. At most, as in Dürer’s ominous version, there will be a discreet stream of blood drawn by the superficial piercing of the sword. Yet, there is not even a hint of violence in this painting attributed to Pencz. The surreal atmosphere seems wholly at odds with the tragic end that befalls Lucretia. Dürer, despite the heavily criticised composition of his Lucretia, does manage to imbue the work with an atmosphere of great solemnity and foreboding that seems to be curiously absent in both Cranach’s version and the present work.

It is likely that Cranach viewed Lucretia as he did the other heroines whom he frequently depicted such as Judith, the Old Testament heroine, and Salome, the wife of King Herod: as an iconic figure and the embodiment of virtue rather than one based in historical myth, or indeed reality. This is perhaps in no small part due to the erotic nature of Cranach’s nudes and this idea can certainly be transposed onto the present Lucretia.

Whilst not as flamboyantly dressed as some of Cranach’s versions, the present work shows a woman surrounded by luxury and dripping with ornate and precious jewellery. The intricate detailing of her pendant and bracelets bear a distinctly Northern European flavour and have far more in common with versions by Cranach. Arguably, the artist’s decision to clothe his subject in little else but jewellery reveals a startling contradiction: on the one hand, she historically embodies the wifely virtues that Lucretia herself exemplified, while in the other, she is presented to us in a suggestive pose. It is highly similar in this respect to Pencz’s female nude previously discussed. Such playful eroticism is entirely missing from Dürer’s 1518 version. Interestingly, however, the backdrop of Lucretia’s bedroom, which is not included by Cranach, is borrowed in the present work from Dürer’s careful intimation of drapery.

Pencz himself evidently derived much inspiration from the story as he painted at least one other version of Lucretia on the point of suicide. In addition, as part of a selection of engravings from Roman history, Pencz includes the scene when Tarquinius surprises the sleeping Lucretia, threatening her with his sword if she makes a single noise. The stylistic similarities between the present work and Pencz’s engravings are exemplified in his rendition of the story of Paris and Oenone from 1539. The voluptuous figure of Oenone and the luxurious drapery that conceals very little are strongly reminiscent of the figure of Lucretia. The facial expressions of the two women are highly similar even though Oenone is composed in profile.

Pencz was a German draughtsman and painter who was active in the workshop of Dürer. He arrived in Nuremberg in 1523 and subsequently entered Dürer’s workshop. Imprisoned, together with the Beham brothers, for allegedly disseminating the radical political and religious views of Thomas Müntzer, he was eventually pardoned and free to carry on with his painting. Heavily influenced by his master, Pencz’s prints of the 1520s include copies after prints by Dürer, employing the fashionable northern Italian style. Pencz was probably in northern Italy and Venice in the late 1520s and returned to Nuremberg in c.1529. Works by Venetian artists exerted a great deal of influence upon him. Similarly, a painting of Judith (Alte Pinakothek, Munich) shows a half-length figure inthe manner of the early work of Palma Vecchio (?1479/80-1528) or Titian (c.1485/90-1576).

In the years following 1533, Pencz made several large ceiling pictures on canvas and was one of the first in Germany to conceive of ceiling pictures as a continuous whole. He was commissioned by Hirschvogel to do a ceiling painting of the Fall of Phaethon (preparatory drawing, Nuremberg), for the main room of the Bolognese Renaissance-style house built in his pleasure grounds. Peter Flötner (1485/96-1546) provided the interior decoration, and Pencz’s painting was clearly influenced by the furnishing and decoration by Giulio Romano (?1419-1546) of the Palazzo del Te, Mantua, which he saw when he visited Italy in the late 1520s.

Pencz completed a prestigious commission from King Sigismund I of Poland to paint scenes from the Passion (1538) for the silver altarpiece in the Jagiellonian chapel in Wawel Cathedral, Kraków (in situ), unfinished after the death of the court painter Hans Dürer (1490-?1538).

Between 1539 and 1540, Pencz seemingly made a second journey to Italy, going as far as Rome. There are many indications of this in his surviving drawings and engraved prints from the period. A revisit to Mantua is indicated by the large engraving of the Capture of Carthage after Romano’s work of 1539. This second Italian journey also affected Pencz’s religious and mythological paintings, which mostly contain a few figures shown half-length in the Venetian style.

In September 1550 the Prussian Duke Albert sent for him to come to Königsberg as a court painter, at the instigation of the preacher Andreas Osiander, whose portrait Pencz had painted in 1544. He set out but died en route.

We are grateful to Mr. Jan de Maere for the attribution of the work to Georg Pencz.

¹ Livy Ab Urbe Condita I.57-60.

Dimension: 74 x 104 cm (29¹/₁₀ x 40⁹/₁₀ inches)

More artworks from the Gallery