Marketplace

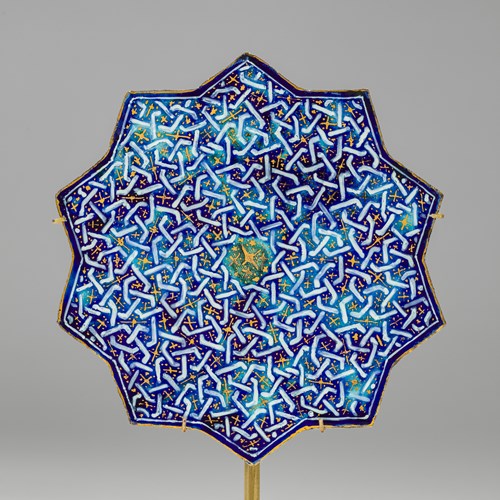

QAJAR TABLETOP

Fritware tiles with cobalt blue backgrounds, mauve and yellow costumes, and turquoise highlights, painted under transparent glaze, were produced during the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925). The most abundant examples of Qajar tiles are rectangular, with a width of circa 25cm, featuring one or two figures. In the mid-19th century, Qajar tiles began to be sold purely for display rather than for use in multi-part friezes. They featured more figures, often representing scenes from literature and culture. Popular themes included the Shahnameh and Khamsa of Nizami.1 Though this object is mounted with a hook, its size and shape suggest that it was intended for use as a tabletop rather than a display tile. Of similar dimensions and featuring a white border decorated with split-leaf foliate, palmettes, and dots, another Qajar tabletop is held in the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (accession no. 2016.13.11) and is illustrated in Qajar Ceramics.2 The origin of setting ceramic panels into tabletops, mounted on four legs or a central pedestal, lies in 18th century western Europe.3 Those made by Sèvres, examples of which can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (accession nos 1975.1.2032 and 1975.1.2028), were particularly popular. Tables topped with Qajar ceramic panels therefore made popular diplomatic gifts to Western recipients. A tabletop originating from 1887-1888 Tehran, now in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (accession no. 559:1 to 9-1888), has an inscription stating that it was commissioned by Major General Sir Robert Murdoch Smith, Director of the Persian Telegraph Department from 1865 to 1888.

The scene depicted is one of courtly celebration. On the left-hand side of the image a woman carries an overflowing basket of fruit above her head, a symbol of abundance and prosperity. Next to her stands a falconer, a figure commonly seen on Qajar tiles. Falconry was a sport enjoyed by the elite of Iranian society through the centuries, and its inclusion distinguishes this gathering as one of the nobility or royalty. Musicians play the tar, a Persian stringed instrument, and the ney, an end-blown flute. A dancer is performing a Motrebi dance, sometimes known as the ‘glass dance’ or the ‘vase dance’, because dancers sometimes held implements such as goblets, vases, and ewers.4 A tile in the collection of the IAMM (accession no. 2016.13.17) features the same configuration of musicians playing the tar and the ney, and a Motrebi dancer. That this dance was strictly performed by men or female impersonators, known as zan push, may explain why the dancer is wearing male clothing but a female headdress. In the foreground, two young men sit and listen to a Sufi scholar, fuelled by food from a ceramic pot.

1 Nayel Barakat, Heba, and Zahra Khademi. Qajar Ceramics: Bridging Tradition and Modernity. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, 2019. 81.

2 Ibid. 130.

3 Ibid. 130.

4 Ameri, Azardokht, ‘Iranian Urban Popular Social Dance and So-Called Classical Dance: A Comparative Investigation in the District of Tehran’, Dance Research Journal 38.1/2 (2006), 163-179. 165.

The scene depicted is one of courtly celebration. On the left-hand side of the image a woman carries an overflowing basket of fruit above her head, a symbol of abundance and prosperity. Next to her stands a falconer, a figure commonly seen on Qajar tiles. Falconry was a sport enjoyed by the elite of Iranian society through the centuries, and its inclusion distinguishes this gathering as one of the nobility or royalty. Musicians play the tar, a Persian stringed instrument, and the ney, an end-blown flute. A dancer is performing a Motrebi dance, sometimes known as the ‘glass dance’ or the ‘vase dance’, because dancers sometimes held implements such as goblets, vases, and ewers.4 A tile in the collection of the IAMM (accession no. 2016.13.17) features the same configuration of musicians playing the tar and the ney, and a Motrebi dancer. That this dance was strictly performed by men or female impersonators, known as zan push, may explain why the dancer is wearing male clothing but a female headdress. In the foreground, two young men sit and listen to a Sufi scholar, fuelled by food from a ceramic pot.

1 Nayel Barakat, Heba, and Zahra Khademi. Qajar Ceramics: Bridging Tradition and Modernity. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, 2019. 81.

2 Ibid. 130.

3 Ibid. 130.

4 Ameri, Azardokht, ‘Iranian Urban Popular Social Dance and So-Called Classical Dance: A Comparative Investigation in the District of Tehran’, Dance Research Journal 38.1/2 (2006), 163-179. 165.

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie

_T638839371969721990.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)

Ionia_T638206163534868960.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)