Marketplace

Pair of Carvings of Incarnations of Vishnu

The Dashavatara are the ten primary avatars of Vishnu. Though the list varies across different sects, the most standard is the following: Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Parashurama, Rama, Krishna or Balarama, Buddha or Krishna, and Kalki.1 These two carvings depict Varaha (pictured right) and Kalki (pictured left) and were presumably part of a series of ten.

Varaha is the third avatar of Vishnu. He is always represented as a human with the head of a boar.2 When the demon Hiranyaksha dragged the Earth in the form of the goddess Bhumi to the bottom of the cosmic ocean, Vishnu took the form of a boar to rescue her. He fought the demon for a thousand years, eventually slaying it and then raising the earth from the water on his tusks.3 Kalki is Vishnu’s prophesied tenth and final avatar. He will appear at the end of the present age, in the year 428,898 AD, to bring about a return to righteousness (dharma).4 Though Kalki is a human avatar who will ride a white horse named Devadatta, many carved depictions merge the two, giving Kalki a horse’s face.5

This style of intricate carving comes from Mysore, Karnataka. It emulates the lacy stye of the 12th-14th century Hoysala Kingdom of the Deccan, which is characterised by layers of intricate detail and deep undercutting.6 Figures are festooned with elaborate jewellery: head ornaments, earrings, shoulder tassels, chokers, long necklaces, anklets, bracelets, and garlands.7 Fine stone carvings in this style adorn the outer walls of many temples in Karnataka, including the Hoysaleshvara Temple in Halebid, the former capital of the Hoysalas, and the Chennakesava Temple in Belur. Both of these temples feature carvings of the avatars of Vishnu (see accession no. INC1261 in the University of Washington Libraries for the carving of Varaha at Belur).8 Carvings in this style in sandalwood proliferated in the mid 19th to early 20th centuries, possibly due to the patronage of the rulers of Mysore. The Maharajas of Mysore sent examples of sandalwood carvings to international exhibitions, where they were described as the ‘most perfect samples'.9

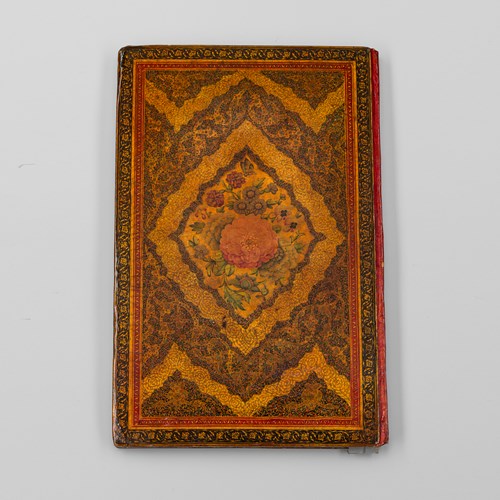

A sandalwood model of a Hindu temple with deities housed in niches is held in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (accession no. IM.321-1924). It was made in Mysore between 1900 and 1923 and displayed at the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley in 1924. Not only does it feature the same style of layered lacy carving as the present example, but the deities are also presented on similar plinths to the carvings of Varaha and Kalki. The dress, with tall crowns, ornate jewellery, and garlands, is also comparable. A sandalwood album case in the Royal Collection Trust, London (accession no. RCIN 90629), which was presented to King Edward VII in Mysore in 1875, is carved in the same style with Hindu deities.

These carvings were acquired by Lieutenant General William George Gold (1800-1868) of Garthmyl Hall, Montgomeryshire, and have been in the family ever since. Lieutenant Gold served in India in the 53rd Shropshire Regiment, receiving the Sutlej medal in 1846 for his service at the Battle of Aliwal during the First Anglo-Sikh War. Later that year, he served at the Battle of Sobraon, sustaining an injury which would send him back to England. He likely purchased these carved avatars of Vishnu as a souvenir of his time in India. That these carvings are labelled – ‘Varaha (Pig)’ and ‘Kulki (Horse)’ – with transliterations of the Sanskrit names and with the English names of the animals, supports the idea that they were made for an English-speaking client with little knowledge of Hinduism.

[1] Raikar, Sanat Pai. ‘Dashavatara’, Encylopaedia Britannica, 7 Jul. 2023. Retrieved online 18 July 2024 via https://www.britannica.com/topic/dashavatara

[2] Bhattacharyya, A.K. The Iconography of Hindu Images. Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, 2019. P. 231.

[3] Storm, Rachel. Indian Mythology: Myths and Legends of India, Tibet and Sri Lanka. London: Anness Publishing, 2000. p. 48.

[4] Ibid. p. 49.

[5] Dalal, Roshen. Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. London: Penguin, 2014. p. 188.

[6] Dye, Joseph M. (III). The Arts of India. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2001. pp. 174, 176.

[7] Ibid. p. 63.

[8] Photographed by Krishna C. Gairola between 1968 and 1999.

[9] Watt, G. Indian Art at Delhi, being the official catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903. Calcutta: 1903, p. 150 in Meghani, Kajal. Splendours of the Subcontinent: A Prince’s Tour of India 1875-6. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2017. p. 202.

Varaha is the third avatar of Vishnu. He is always represented as a human with the head of a boar.2 When the demon Hiranyaksha dragged the Earth in the form of the goddess Bhumi to the bottom of the cosmic ocean, Vishnu took the form of a boar to rescue her. He fought the demon for a thousand years, eventually slaying it and then raising the earth from the water on his tusks.3 Kalki is Vishnu’s prophesied tenth and final avatar. He will appear at the end of the present age, in the year 428,898 AD, to bring about a return to righteousness (dharma).4 Though Kalki is a human avatar who will ride a white horse named Devadatta, many carved depictions merge the two, giving Kalki a horse’s face.5

This style of intricate carving comes from Mysore, Karnataka. It emulates the lacy stye of the 12th-14th century Hoysala Kingdom of the Deccan, which is characterised by layers of intricate detail and deep undercutting.6 Figures are festooned with elaborate jewellery: head ornaments, earrings, shoulder tassels, chokers, long necklaces, anklets, bracelets, and garlands.7 Fine stone carvings in this style adorn the outer walls of many temples in Karnataka, including the Hoysaleshvara Temple in Halebid, the former capital of the Hoysalas, and the Chennakesava Temple in Belur. Both of these temples feature carvings of the avatars of Vishnu (see accession no. INC1261 in the University of Washington Libraries for the carving of Varaha at Belur).8 Carvings in this style in sandalwood proliferated in the mid 19th to early 20th centuries, possibly due to the patronage of the rulers of Mysore. The Maharajas of Mysore sent examples of sandalwood carvings to international exhibitions, where they were described as the ‘most perfect samples'.9

A sandalwood model of a Hindu temple with deities housed in niches is held in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (accession no. IM.321-1924). It was made in Mysore between 1900 and 1923 and displayed at the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley in 1924. Not only does it feature the same style of layered lacy carving as the present example, but the deities are also presented on similar plinths to the carvings of Varaha and Kalki. The dress, with tall crowns, ornate jewellery, and garlands, is also comparable. A sandalwood album case in the Royal Collection Trust, London (accession no. RCIN 90629), which was presented to King Edward VII in Mysore in 1875, is carved in the same style with Hindu deities.

These carvings were acquired by Lieutenant General William George Gold (1800-1868) of Garthmyl Hall, Montgomeryshire, and have been in the family ever since. Lieutenant Gold served in India in the 53rd Shropshire Regiment, receiving the Sutlej medal in 1846 for his service at the Battle of Aliwal during the First Anglo-Sikh War. Later that year, he served at the Battle of Sobraon, sustaining an injury which would send him back to England. He likely purchased these carved avatars of Vishnu as a souvenir of his time in India. That these carvings are labelled – ‘Varaha (Pig)’ and ‘Kulki (Horse)’ – with transliterations of the Sanskrit names and with the English names of the animals, supports the idea that they were made for an English-speaking client with little knowledge of Hinduism.

[1] Raikar, Sanat Pai. ‘Dashavatara’, Encylopaedia Britannica, 7 Jul. 2023. Retrieved online 18 July 2024 via https://www.britannica.com/topic/dashavatara

[2] Bhattacharyya, A.K. The Iconography of Hindu Images. Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, 2019. P. 231.

[3] Storm, Rachel. Indian Mythology: Myths and Legends of India, Tibet and Sri Lanka. London: Anness Publishing, 2000. p. 48.

[4] Ibid. p. 49.

[5] Dalal, Roshen. Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. London: Penguin, 2014. p. 188.

[6] Dye, Joseph M. (III). The Arts of India. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2001. pp. 174, 176.

[7] Ibid. p. 63.

[8] Photographed by Krishna C. Gairola between 1968 and 1999.

[9] Watt, G. Indian Art at Delhi, being the official catalogue of the Delhi Exhibition, 1902-1903. Calcutta: 1903, p. 150 in Meghani, Kajal. Splendours of the Subcontinent: A Prince’s Tour of India 1875-6. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2017. p. 202.

Provenance:

More artworks from the Gallery