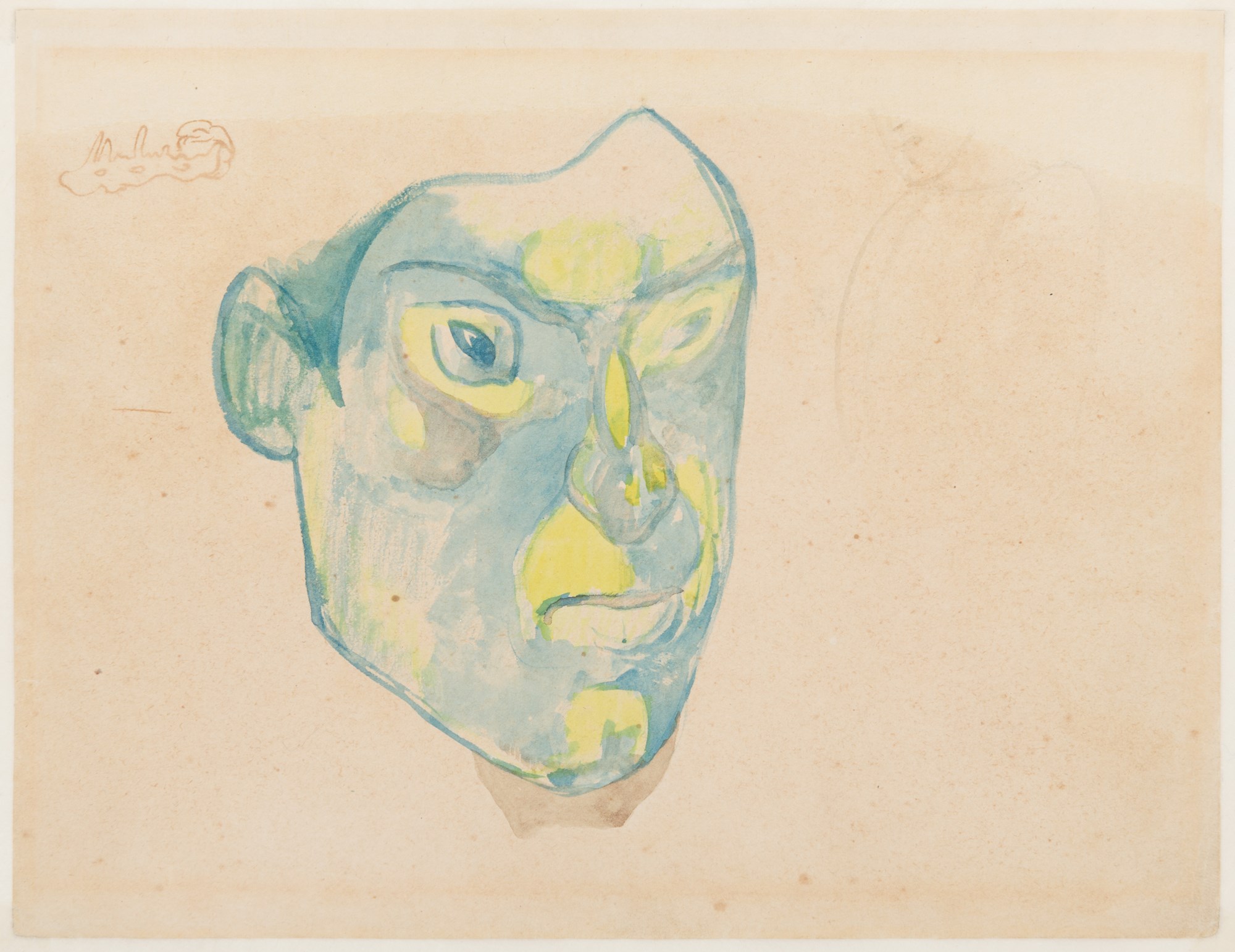

This striking drawing may have been a preparatory study, albeit in reverse, for a small painting on silk of this Breton period, Nirvana: Portrait of Meijer de Haan, painted by Gauguin at Le Pouldu in c.1890 and today in the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. This enigmatic painting depicts the Dutch painter, with distorted features and slanted, almond-shaped eyes, in front of a composite of elements of two recent Breton canvases by Gauguin of 1889. In Nirvana, Gauguin’s astonishing treatment of de Haan’s face, ‘with its mixture of fox-like, satanic qualities combined with the rapt expression suggestive of mystical insight’, is by far the most striking feature of the painting and has led to numerous scholarly theories about its significance. The present sheet bears a number of similarities to the mask-like face of Meijer de Haan in Nirvana, notably the almond-shaped eyes and nose picked out in blue tones and the acidic, greenish-yellow highlights applied to the eyebrows and upper lip.

During this Breton period Gauguin painted another, perhaps slightly earlier, portrait of Meijer de Haan, in which the Dutchman is depicted in front of a table with books, a lamp and a bowl of apples. Originally installed in the dining room of the inn at Le Pouldu, the painting is now in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which also houses a related watercolour version of the same composition. Gauguin also carved and painted a very large (indeed, over life-size) wooden bust of de Haan for the dining room at Le Pouldu, which is now in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

For most of his life Meijer de Haan suffered from tuberculosis, which stunted his growth and led to his developing a hunchback. He was deeply interested in occult literature and arcane beliefs, and it may have been partly for this reason that Gauguin seems to have chosen to exaggerate the Dutchman’s physiognomy - often giving him a somewhat diabolical presence - in his various depictions of him. As the scholar John Rewald has noted, ‘Gauguin was fascinated with his friend’s startling features and later represented them in various Tahitian paintings.’ Similarly, Françoise Cachin has written that ‘the tortured mask of Meyer de Haan seems to have haunted [Gauguin] for the remainder of his life.’ A portrait of the Dutchman appears in a wood engraving executed by Gauguin in Tahiti in c.1896-1897, an impression of which he pasted into the handwritten manuscript of his journal Noa Noa now in the Louvre.

Several years after de Haan’s death, Gauguin included images of him in two late paintings. The mask-like head of his late friend appears in the background of a still life of a bouquet of flowers painted in Tahiti around 1899, now in a private collection, while a strikingly menacing figure of de Haan, with claw-like feet and a demonic countenance, is prominent in one of Gauguin’s final paintings, the large Contes Barbares (Primitive Tales) of 1902, today in the Museum Folkwang in Essen. As a modern scholar has noted of the latter canvas, ‘It is clear that Gauguin was haunted by the features of this strange, dwarflike painter, whom he represented as a leering figure, at once faun and devil…The figure remains one of many deliberate enigmas in Gauguin’s late works.’ Another recent scholar echoes this view, writing that ‘Gauguin could not or would not forget the mysterious presence of the Dutchman’s bizarre face and continued to be haunted to the end of his days by those intense, all-seeing eyes.’

A number of modern scholars have suggested that the present sheet may be a self-portrait by Gauguin, rather than a portrait of Meijer de Haan. As one recent writer has pointed out, ‘the features have little in common with Meyer de Haan’s own Self-Portrait, for example. Meyer de Haan had a rounder head, a beard and a bushy mustache. The drawing does, however, display a conspicuous likeness to Gauguin’s own face, which was longer than that of his friend. He had a distinctively aquiline nose; he too wore a beard and a (better groomed) mustache, but it is more likely that he would portray himself without those attributes than his friend.’ There are indeed some similarities between the mask-like face in the present sheet and a handful of exaggerated self-portrait images by Gauguin in works of the late Breton period of 1889-1890, such as a charcoal drawing in the Musée d’Art moderne et contemporain in Strasbourg and the panel Self-Portrait with Halo, painted in 1889 for the dining room at Le Pouldu and today in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Certainly, the close personal and professional relationship between Gauguin and Meijer de Haan, albeit over a relatively brief period of time in Brittany, as well as the fact that Gauguin continued to depict his friend in works made in French Polynesia after their separation, has led to the suggestion that he may have occasionally used the figure of de Haan as a sort of visual surrogate for the artist himself. As June Hargrove has commented, ‘The series of portraits of De Haan occupies a unique place in Gauguin’s art, manifesting the principles driving his aesthetic philosophy for more than a decade. The accumulated significance of these images speaks to the artist’s calling in modern society. Taken together they not only convey his views on the creative process, they attest to his understanding of art as revelation. Gauguin identified more closely with De Haan than with any other of his peers.’

Referring to the present sheet, Heather Lemonedes has written that, ‘In another watercolor, Self-Portrait, previously thought to be a portrait of Meyer de Haan, yellow…figures prominently. In this drawing, Gauguin’s disembodied face is schematized, rendered with a cloissonnist blue outline and yellow highlights. The drawing underscores Gauguin’s understanding of the law of simultaneous contrast of complementary colors. He would continue to juxtapose blue and yellow is subsequent paintings and drawings.’ Furthermore, as another scholar has pointed out, ‘Originally, in addition to the blue, green and yellow used in the head, there was also a fourth color that would have intensified the contrast still further. Traces of a now-faded pink or red wash can be seen over the entire sheet, and the areas below the right eye and chin would probably have been more pronounced in tone. The pink wash in all likelihood also concealed the two sketches that are now visible once more: a decorative element at top left and a sketchy figure to the right of the portrait.’ This same slight sketch of the head and torso of a figure at the upper right of the present sheet, as John Rewald had suggested, might be related to Gauguin’s drawing of The Head of a Breton Peasant Girl of c.1889, in the collection of the Harvard University Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The first owner of the present sheet was the French painter George-Daniel de Monfried (1856-1929), a close friend of Gauguin. During Gauguin’s time in the South Seas, de Monfried was one of the main links he maintained with France, through an extensive series of letters and works of art sent to him from Tahiti and the Marquesas. De Monfried was appointed the executor of Gauguin’s will after the painter’s death and helped to organized a posthumous exhibition of his work at the Salon d’Automne in 1906.

Provenance: George-Daniel de Monfried, Paris and Saint-Clément

Jean Souze, France

Wildenstein & Co., New York, by 1955

Hammer Galleries, New York

Closson’s Galleries, Cincinnati, Ohio

Acquired from them in November 1968 by Frederic Ziv, Cincinnati, Ohio

The Frederic W. Ziv Trust

Their sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 9 May 2002, lot 140

Galerie Hopkins-Custot, Paris

Acquired from them in 2006 by the Triton Collection Foundation, The Netherlands.

Literature: Victor Segalen and Annie Joly-Segalen, ed., Lettres de Gauguin à Daniel de Monfried, Paris, 1950, illustrated between pp.208 and 209, pl.14 (as Masque); John Rewald, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), New York, 1954, unpaginated, pl.34 (Meyer de Haan); Robert Goldwater, Paul Gauguin, New York, 1957, illustrated p.18 (as a portrait of Meyer de Haan, and dated c.1890); John Rewald, Gauguin Drawings, New York and London, 1958, p.26, no.26, pl.26 (Study for a Portrait of Jacob Meyer de Haan, dated c.1890); Robert Goldwater, Paul Gauguin, Cologne, 1989, illustrated p.18; Stephen F. Eisenman, ed., Paul Gauguin: Artist of Myth and Dream, exhibition catalogue, Rome, 2007-2008, pp.258-259, no.57 (Study for a Portrait of Meyer de Haan); Fred Leeman, Klaroenstoot voor de moderne kunst: de Nabis in de collective van de Triton Foundation / Clarion Call of Modern Art: The Nabis in the Collection of the Triton Foundation, exhibition catalogue, The Hague, 2008, illustrated p.34 (Study for a Portrait of Meyer de Haan); Heather Lemonedes, Belinda Thomson and Agnieszka Juszczak, Paul Gauguin: The Breakthrough into Modernity, exhibition catalogue, Cleveland and Amsterdam, 2009-2010, p.179, no.103 (as a self-portrait by Gauguin); Christopher Lloyd, Impressionism: Pastels, Watercolors, Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Milwaukee, 2011, illustrated in colour p.102, pl.42 (as a self-portrait by Gauguin); Klaus Albrecht Schröder and Christine Ekelhart, ed., Impressionism: Pastels, Watercolours, Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Vienna, 2012, p.162, pl.78 (as a self-portrait by Gauguin); Sjraar van Heugten, Avant-gardes 1870 to the present: The Collection of the Triton Foundation, Brussels, 2012, pp.154-155 and p.547 (as a self-portrait by Gauguin); Sjaar van Heugten and Helewise Berger, Van Gogh’s Inner Circle: Friends, Family, Models, exhibition catalogue, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, 2019-2020, p.115, fig.87 (as a self-portrait by Gauguin).

Exhibition: Long Beach, Municipal Art Center, 1953; Vancouver, Vancouver Art Gallery, The French Impressionists, 1953, no.59; New York, Wildenstein & Co., Timeless Master Drawings, 1955, no.131; London, Wildenstein & Co., The Art of Drawing: XVIth to XIXth Centuries, 1956, no.90; Rome, Complesso del Vittoriano, Paul Gauguin: Artist of Myth and Dream, 2007-2008, no.57; The Hague, Gemeentemuseum, Les Nabis: Works from the Triton Collection, 2008; Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art and Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, Paul Gauguin: The Breakthrough into Modernity, 2009-2010, no.103; Milwaukee, Milwaukee Art Museum, Impressionism: Masterworks on Paper, 2011-2012, no.42; Vienna, Albertina, Impressionism: Pastels, Watercolours, Drawings, 2012, no.78; Rotterdam, Kunsthal, Avant-Gardes: The Collection of the Triton Foundation, 2012-2013; ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Het Noordbrabants Museum, Van Goghs intimi: Vrienden, famille, modellen / Van Gogh’s Inner Circle: Friends, Family, Models, 2019-2020.

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie

_T638451686580251969.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)

_T638636512051387495.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)