According to Bernhard Zeller, all of Hesse's works are ‘fragments of a great self-portrait’ and so one can also discover autobiographical references in the satire about the ‘foreign city’:

The parable-like tale was written during Hesse's time in Montagnola near Locarno, where he had lived since 1919. 5] During his time at Lake Constance, Hesse withdrew from urban society: from 1904 to 1912, the author lived with his first wife Maria in the then very remote village of Gaienhofen in the spirit of his life reform. For the first three years, they rented a simple farmhouse without running water or electricity. In April 1907, Hesse stayed as a guest at the Lebensreform colony on Monte Verità near Ascona and became friends with the dropout and co-founder of the ‘Vegetable Cooperative’ Gusto Gräser.

According to Michels, the story shows Hesse's criticism of the times and civilisation, in particular the perversion of mass tourism and the destruction of the last remaining pristine reserves into a sterile ‘nature’ for the business of tourism, ‘the full force of which, however, is expressed less in the counter-world of the poems than in thousands of letters and book reviews and in over a hundred reflections’.

Adaptation

The holiday wishes of the city dweller

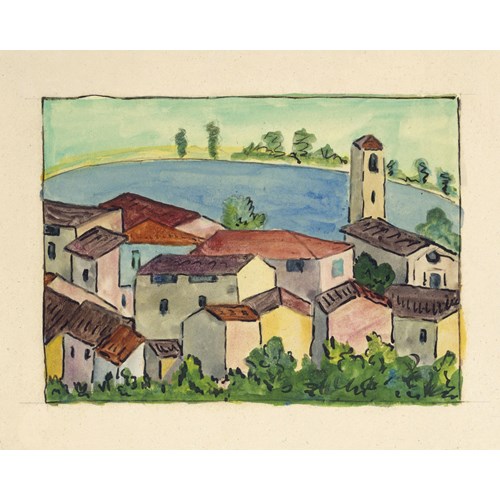

Hesse's story begins with an ironic assessment of the tourist industry: ‘This city is one of the wittiest and most profitable endeavours of the modern spirit.’ Here, ‘all the holiday and nature desires of the average city dweller's soul’ have been realised ‘in ideal perfection’. As the holiday traveller from a metropolis raves about nature, idyll, peace and beauty, but cannot bear it, a substitute for nature has been created for him under the label of ‘authenticity’: a safe, hygienic, denatured nature. In spring and autumn, wealthy city dwellers could travel to the real south with palm trees, blue lakes and picturesque towns surrounded by tamed nature, where they could live hygienically and cleanly and experience a cultivated, sociable city atmosphere with art and music.

The ideal town by the lake

In his description of the tourist town, the narrator collects the cliché images and the guests' thought patterns of an ideal southern town, of which there are dozens of variations: Lake with a promenade flanked by trees, picturesque rowing boats on the quay, Italian sailors with southern eyes and thin cigarettes who can communicate in any other language, a lakeside road running parallel to the waterfront path with a belt of four-storey hotel buildings, the tourist town. Behind it lies the real Italian south with narrow alleyways and squares for the vegetable, meat and fish markets, market criers, barefoot children playing football with tin cans, loud mothers with flying hair, shoemakers' workshops by the roadside, shirt-sleeved, jovial traders peering out of open shop doors, “all genuine and very colourful and original” like in the first act of an opera. The stranger marvels at the foreign soul of the people, takes photographs, buys postcards and tries to speak Italian.

Excursions into the surrogate nature

Behind the city lies the countryside with fields and wild, unpolished nature, just as it has always been. But the strangers only see everything dusty from their passing cars and return to the city from their short excursions. Here they drive along freshly sprayed tarmac roads to the Park Hotel with its attentive manager and well-mannered staff. The guests stroll past antique shops, take cute little steamboats across the lake, meet friends from Frankfurt in the elegant cafés, watch famous poets and popular actresses at press conferences, read local magazines, phone relatives back home, listen to an Italian tenor in the Kursaal, stroll back to the hotel past flowering plants, camellias in tubs and tall palm trees, ‘all real.’ The next morning, you take part in a social trip to -aggio and if you accidentally end up in -iggio or -ino, you will find the same ideal city there with everything ‘that belongs to the life of a city dweller if he wants to have it good.’