Marketplace

Indian Matchlock Rifle (Toradar)

Firearms first arrived in India with the Portuguese in 1498, who brought matchlock muskets and ships armed with cannons.1 The toradar evolved from this technology, and despite the invention of the more efficient wheellock and flintlock mechanisms, the matchlock remained in use in India well into the 19th century.2 In the tradition of the jezail from neighbouring Afghanistan, guns from the Sindh region of India (in modern-day Pakistan) have long barrels and fish-tail butts. The function of its most distinctive feature, the curved stock, is debated, but a possible explanation is that it helped hold the gun under the armpit whilst the bearer rode a horse. The trigger is positioned on the stock, rather than directly below the mechanism, making it an infamously unwieldly weapon.3

Typical of toradars from Sindh, the barrel is made from highly-textured Damascus steel. The barrel is mounted onto the stock with five engraved silver capucines. Silver panels engraved with similar floral and vegetal motifs are applied at the butt and the receiver. Gold koftgari enriches the muzzle, ramrod, and breech. A matchlock rifle in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (accession no. 36.25.2141), dated to the second quarter of the 19th century, shares similar koftgari ornamentation on its Damascus steel barrel. A toradar in the Royal Collections (accession no. RCIN 37887) at Sandringham, from 19th century Sindh, was presented to King Edward VII during his tour of India in 1875. Its stock and butt are similarly ornamented.

Highly unusually for an object of this date, there is an inscription in a Laṇḍā script. Laṇḍā scripts were used in Punjab and parts of North India to write Sindhi, Pashto, Punjabi, Hindustani, Kashmiri, Saraiki, and Balochi, as well as other dialects. They fell out of use in the 19th century in favour of Perso-Arabic scripts and Devangari.

This is the only example known to us of a rifle from Sindh with an inscription in Laṇḍā, rather than Perso-Arabic.

n.b. accession nos are clickable links

1 Gahir, Sunita and Spencer, Sharon (eds). Weapon: A Visual History of Arms and Armor. New York City: DK Publishing, 2006. 156.

2 Ibid. 260.

3 Reddy, Ravinder. Arms & Armour of India, Nepal & Sri Lanka. London: Hali, 2018. 356.

Typical of toradars from Sindh, the barrel is made from highly-textured Damascus steel. The barrel is mounted onto the stock with five engraved silver capucines. Silver panels engraved with similar floral and vegetal motifs are applied at the butt and the receiver. Gold koftgari enriches the muzzle, ramrod, and breech. A matchlock rifle in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (accession no. 36.25.2141), dated to the second quarter of the 19th century, shares similar koftgari ornamentation on its Damascus steel barrel. A toradar in the Royal Collections (accession no. RCIN 37887) at Sandringham, from 19th century Sindh, was presented to King Edward VII during his tour of India in 1875. Its stock and butt are similarly ornamented.

Highly unusually for an object of this date, there is an inscription in a Laṇḍā script. Laṇḍā scripts were used in Punjab and parts of North India to write Sindhi, Pashto, Punjabi, Hindustani, Kashmiri, Saraiki, and Balochi, as well as other dialects. They fell out of use in the 19th century in favour of Perso-Arabic scripts and Devangari.

This is the only example known to us of a rifle from Sindh with an inscription in Laṇḍā, rather than Perso-Arabic.

n.b. accession nos are clickable links

1 Gahir, Sunita and Spencer, Sharon (eds). Weapon: A Visual History of Arms and Armor. New York City: DK Publishing, 2006. 156.

2 Ibid. 260.

3 Reddy, Ravinder. Arms & Armour of India, Nepal & Sri Lanka. London: Hali, 2018. 356.

More artworks from the Gallery

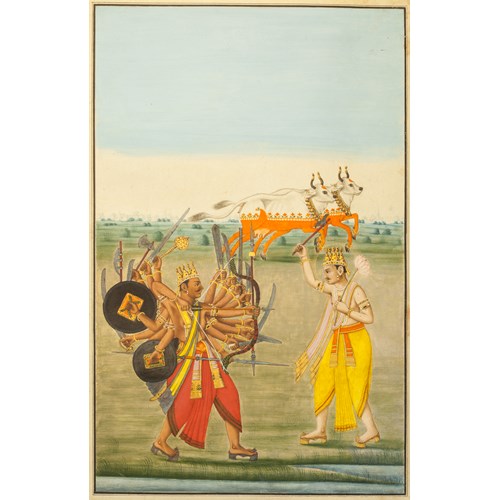

_T638491371114922044.jpg?width=2000&height=2000&mode=max&scale=both&qlt=90)

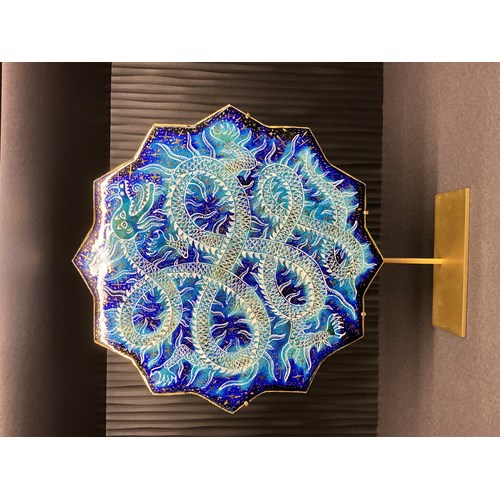

_T638671088209735808.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)