Marketplace

Dancer on a Terrace

Dancer on a Terrace

Date c. 1800

Epoque Early 19th century

Origine Western India (or Canton, China)

Dimension 39.5 x 34.5 cm (15¹/₂ x 13⁵/₈ inches)

Made for the Indian market

Reverse glass painting in original Chinese gilt frames in the style of Louis XVI

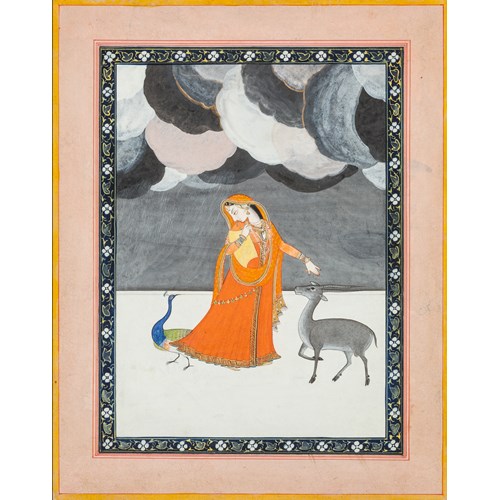

The painting depicts a young female dancer on a terrace in an elaborately detailed costume. Her white, luminous skin has light pink shading on the inside of her elbows and palms of her hands; the right-hand side of her face is also delicately shaded. She is wearing a pink, open bodice with three-quarter sleeves and ornate edgings. Thin jewelled armbands with tassels are attached to both sleeves. She has a matching gold necklace with a ruby surrounded by pearls, a long necklace ornamented with white pearls and bangles on her arms. The gathered skirt is made of diaphanous material with floral patterns and an embroidered hem; a scarf with ornate edgings hangs from her right shoulder down her back. The toes are painted pink, and she wears thin gold anklets. Her long black hair has a jewel as a decoration. Both the costume and jewellery are Indian; floral patterns like those on her skirt are depicted in many Indian miniatures from the 17th century onwards as is the jewellery (for armbands and a necklace with tassels, see c. 1750–75 Pahari miniature in Goswamy and Fischer, p. 187. For similarly portrayed floral textile patterns and a scarf, see an Indian miniature painting from Farrukhabad, Avadh, dated to 1770, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001.421).

The abstract motifs on the carpet resemble Chinese scrolling clouds, and the floor tiles have a dark blue pattern popularly found in Indian textiles and art. Behind the blue stone balustrade are pink peonies, camellias and other red flowers amidst lush greenery. The sky is painted in hues of blue and white.

The facial features of the dancer, with her soft, almond-shaped eyes and luminous skin, are Chinese inspired. The Chinese influence is also evident on the carpet and on the flowers in the background. Scenes set on a terrace with a stone balustrade are often depicted in Indian miniature paintings where the balustrade acts as a spatial divider.

Our painting has many similarities to a late 18th century reverse glass painting from India, Nawab Namdar Tegh Beg Khan Bahadur (1790–91) at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. In this painting, the governor and his servant are depicted on a terrace with a stone balustrade; in addition, both the carpet and the tiled floor with a dark blue pattern are almost identical to those in our painting. Furthermore, behind the stone balustrade there are pink and red flowers, and the sky is depicted in tones of blue and white similar to our painting.

Part of A Series of Reverse Glass Paintings.

These six reverse glass paintings were produced by Chinese artists for an elite Indian clientele. There was not only a high demand for Chinese reverse glass paintings in Europe and America, but they were also exported from the mid-18th century onwards to the west coast of India by Parsi traders. By the late-18th century Chinese commercial artists had settled in western India to produce such paintings. These included Chinese artists who were employed at the royal courts of the princely states, for example, Kutch and Mysore.

The reverse glass painting technique originated in 15th–16th century Europe, and it is thought that Jesuit missionaries introduced it to China, where reverse glass paintings were made as early as the 1730s. They became very popular in the Chinese export art trade, which began in the 18th century and reached its height between 1800–1850, catering for the demand in the West for paintings and porcelain made in China. Guangzhou (Canton) was the centre of production for export art, including reverse glass paintings.

In export art, the Chinese artists applied European visual representation together with Chinese artistic features. Thus, the end result was a hybrid product made to meet Western demand and taste for the exotic but with some familiar characteristics to the intended viewer. As the term implies, in reverse glass paintings, the artist paints the image in reverse on the back of a sheet of glass, using a master drawing to transpose the outline, to which colours were applied, beginning with any shading and highlighting and followed by the body colour. At the end of the process, the glass is turned over and the finished picture is viewed from the front, unpainted side of the glass.

References:

Audric, Thierry. Chinese Reverse Glass Painting 1720–1820: An Artistic Meeting Between China and the West. Peter Lang, London. 2020.

Clunas, Craig. Chinese Export Watercolours, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. 1984.

Conner, Patrick. The China Trade. 1600–1860. The Royal Pavilion, Art Gallery and Museums, Brighton. 1986.

Crossman, Carl. The Decorative Arts of the China Trade. The Antique Collector’s Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk. 1991.

Dallapiccola, Anna. Reverse Glass Painting in India. Niyogi Books, India. 2017.

Eswarin, R. (ed. and trans.) Reverse Paintings on Glass. The Ryser Collection. The Corning Museum of Glass, New York. 1992.

Goswamy, B.N and Fischer E. Pahari Masters. Court Painters of Northern India. Artibus Asiae Publishers, Zurich. 1992.

Granoff, P. “Reverse Glass Paintings from Gujarat in a Private Canadian Collection: Documents of British India”, Artibus Asiae, vol. 40, no. 2/3, 1978, pp. 204–14.

Pal, P. Indian Painting, Volume I, 1000–1700. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1993.

van der Poel, Rosalien. Made for Trade – Made in China. Chinese export paintings in Dutch collections: art and commodity. University of Leiden, 2016.

Thampi, Madhavi. Sino-Indian Cultural Diffusion through Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Collège de France, Paris, 2020. https://books. openedition.org/cdf/7541?lang=en

Zebrowski, Mark. Deccani Painting. Sotheby Publications, London. 1983.

Stock No.: A5223

Reverse glass painting in original Chinese gilt frames in the style of Louis XVI

The painting depicts a young female dancer on a terrace in an elaborately detailed costume. Her white, luminous skin has light pink shading on the inside of her elbows and palms of her hands; the right-hand side of her face is also delicately shaded. She is wearing a pink, open bodice with three-quarter sleeves and ornate edgings. Thin jewelled armbands with tassels are attached to both sleeves. She has a matching gold necklace with a ruby surrounded by pearls, a long necklace ornamented with white pearls and bangles on her arms. The gathered skirt is made of diaphanous material with floral patterns and an embroidered hem; a scarf with ornate edgings hangs from her right shoulder down her back. The toes are painted pink, and she wears thin gold anklets. Her long black hair has a jewel as a decoration. Both the costume and jewellery are Indian; floral patterns like those on her skirt are depicted in many Indian miniatures from the 17th century onwards as is the jewellery (for armbands and a necklace with tassels, see c. 1750–75 Pahari miniature in Goswamy and Fischer, p. 187. For similarly portrayed floral textile patterns and a scarf, see an Indian miniature painting from Farrukhabad, Avadh, dated to 1770, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001.421).

The abstract motifs on the carpet resemble Chinese scrolling clouds, and the floor tiles have a dark blue pattern popularly found in Indian textiles and art. Behind the blue stone balustrade are pink peonies, camellias and other red flowers amidst lush greenery. The sky is painted in hues of blue and white.

The facial features of the dancer, with her soft, almond-shaped eyes and luminous skin, are Chinese inspired. The Chinese influence is also evident on the carpet and on the flowers in the background. Scenes set on a terrace with a stone balustrade are often depicted in Indian miniature paintings where the balustrade acts as a spatial divider.

Our painting has many similarities to a late 18th century reverse glass painting from India, Nawab Namdar Tegh Beg Khan Bahadur (1790–91) at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. In this painting, the governor and his servant are depicted on a terrace with a stone balustrade; in addition, both the carpet and the tiled floor with a dark blue pattern are almost identical to those in our painting. Furthermore, behind the stone balustrade there are pink and red flowers, and the sky is depicted in tones of blue and white similar to our painting.

Part of A Series of Reverse Glass Paintings.

These six reverse glass paintings were produced by Chinese artists for an elite Indian clientele. There was not only a high demand for Chinese reverse glass paintings in Europe and America, but they were also exported from the mid-18th century onwards to the west coast of India by Parsi traders. By the late-18th century Chinese commercial artists had settled in western India to produce such paintings. These included Chinese artists who were employed at the royal courts of the princely states, for example, Kutch and Mysore.

The reverse glass painting technique originated in 15th–16th century Europe, and it is thought that Jesuit missionaries introduced it to China, where reverse glass paintings were made as early as the 1730s. They became very popular in the Chinese export art trade, which began in the 18th century and reached its height between 1800–1850, catering for the demand in the West for paintings and porcelain made in China. Guangzhou (Canton) was the centre of production for export art, including reverse glass paintings.

In export art, the Chinese artists applied European visual representation together with Chinese artistic features. Thus, the end result was a hybrid product made to meet Western demand and taste for the exotic but with some familiar characteristics to the intended viewer. As the term implies, in reverse glass paintings, the artist paints the image in reverse on the back of a sheet of glass, using a master drawing to transpose the outline, to which colours were applied, beginning with any shading and highlighting and followed by the body colour. At the end of the process, the glass is turned over and the finished picture is viewed from the front, unpainted side of the glass.

References:

Audric, Thierry. Chinese Reverse Glass Painting 1720–1820: An Artistic Meeting Between China and the West. Peter Lang, London. 2020.

Clunas, Craig. Chinese Export Watercolours, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. 1984.

Conner, Patrick. The China Trade. 1600–1860. The Royal Pavilion, Art Gallery and Museums, Brighton. 1986.

Crossman, Carl. The Decorative Arts of the China Trade. The Antique Collector’s Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk. 1991.

Dallapiccola, Anna. Reverse Glass Painting in India. Niyogi Books, India. 2017.

Eswarin, R. (ed. and trans.) Reverse Paintings on Glass. The Ryser Collection. The Corning Museum of Glass, New York. 1992.

Goswamy, B.N and Fischer E. Pahari Masters. Court Painters of Northern India. Artibus Asiae Publishers, Zurich. 1992.

Granoff, P. “Reverse Glass Paintings from Gujarat in a Private Canadian Collection: Documents of British India”, Artibus Asiae, vol. 40, no. 2/3, 1978, pp. 204–14.

Pal, P. Indian Painting, Volume I, 1000–1700. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1993.

van der Poel, Rosalien. Made for Trade – Made in China. Chinese export paintings in Dutch collections: art and commodity. University of Leiden, 2016.

Thampi, Madhavi. Sino-Indian Cultural Diffusion through Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Collège de France, Paris, 2020. https://books. openedition.org/cdf/7541?lang=en

Zebrowski, Mark. Deccani Painting. Sotheby Publications, London. 1983.

Stock No.: A5223

Date: c. 1800

Epoque: Early 19th century

Origine: Western India (or Canton, China)

Dimension: 39.5 x 34.5 cm (15¹/₂ x 13⁵/₈ inches)

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie

_T638839371654308163.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)

_T638772015617641557.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)