Marketplace

Christ at the Column

Corneille Van Clève

Christ at the Column

Date c.1700

Medium Bronze

Dimension 42 x 13 x 12 cm (16¹/₂ x 5¹/₈ x 4³/₄ inches)

Corneille van Clève was born in Paris in 1646 to a family of Flemish goldsmiths. His grandfather, a merchant goldsmith, emmigrated to Paris from Flanders and was naturalised in 1606. Van Clève studied under the French sculptor Francois Anguier and received the Prix de Rome scholarship in 1671. After spending several years at the French Academy in Rome, as well as three years in Venice, he returned to France in 1678. In 1681, he was formally accepted to the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture upon submission of a marble statue of the cyclops, Polyphemus. He would become the director of the Académie from 1711 to 1714, and enjoyed the patronage of both King Louis XIV and XV, earning the King's pension until his death and sculpting numerous statues for the Palace of Versailles.

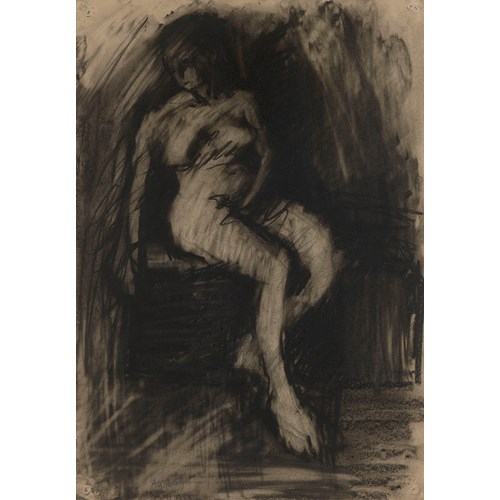

The present work depicts Christ in contrapposto, caught in mid-movement in a serpentine pose; his weight shifted onto his left leg, head turned downward in anguish and his arms tied behind his back with ropes. The form of this bronze bears striking similarities to two early 17th century models in particular; Francois Duquesnoy’s Christ Bound, executed in the 1620s, Alessandro Algardi’s The Flagellation, also executed in the 1620s and more contemporaneously, Francois Girardon’s Christ at the Column dating to approximately c.1700.

The fluidity of movement in this model may suggest that there was a painterly reference which inspired Van Clève’s composition. It is possible that Guido Reni’s Christ at the Column, painted in Rome in about 1603, was seen by Van Clève when he journeyed there in the early 1670s. Both figures are poised in movement, they seemingly step forward with one foot raised and in contrapposto. Their hands bound to the column behind them with their gaze turned downward. Reni’s Christ clearly shows the strong influence of Caravaggio, active in Rome at the time, in particular his mastery of chiaroscuro. It follows in the wake of The Council of Trent (1545-63), which sought to stem the rise of Protestantism with Counter-Reformatory propaganda in art. The focus being on Christ’s suffering and the importance of mainting the Catholic faith.

The power of this bronze lies in the simplicity of its composition. We are immediately transfixed by Christ’s condition, the expression of his suffering by his downturned gaze, without the distraction of the flagellators who might have flanked him. It is a severe rendition of the Catholic, Counter-Reformatory message without superfluousness. Christ’s hair and beard are finely modelled and hand-finished with a hammered surface. The musculature of his lean body is accurately studied and defined. It is a bronze cast of the highest quality, typical of the facture of similar bronzes emerging from the foundries of Paris in circa 1700. During this period in France artists were more frequently working to international but also state-imposed artistic conventions, resulting in a high degree of homogeneity in the finished products.,

The attribution to Corneille van Clève has arisen in comparison to his Leda and the Swan, now in The Louvre, which bears striking similarities to the present bronze Christ. The similarity in the treatment and finishing of the hair, eyelids, lips and drapery is marked, particularly the facture as both are raised on similar square-section bases. The positioning of both figures as they seemingly pace forward, one leg bent and foot raised in contrapposto furthers this point. The slender, athletic forms differ from the more squat examples of Duquesnoy and Girardon’s figures. Therefore, whilst the attribution to Van Clève is not altogether certain, the degree of homogeneity between the present example and Leda and the Swan is significant.

The present work depicts Christ in contrapposto, caught in mid-movement in a serpentine pose; his weight shifted onto his left leg, head turned downward in anguish and his arms tied behind his back with ropes. The form of this bronze bears striking similarities to two early 17th century models in particular; Francois Duquesnoy’s Christ Bound, executed in the 1620s, Alessandro Algardi’s The Flagellation, also executed in the 1620s and more contemporaneously, Francois Girardon’s Christ at the Column dating to approximately c.1700.

The fluidity of movement in this model may suggest that there was a painterly reference which inspired Van Clève’s composition. It is possible that Guido Reni’s Christ at the Column, painted in Rome in about 1603, was seen by Van Clève when he journeyed there in the early 1670s. Both figures are poised in movement, they seemingly step forward with one foot raised and in contrapposto. Their hands bound to the column behind them with their gaze turned downward. Reni’s Christ clearly shows the strong influence of Caravaggio, active in Rome at the time, in particular his mastery of chiaroscuro. It follows in the wake of The Council of Trent (1545-63), which sought to stem the rise of Protestantism with Counter-Reformatory propaganda in art. The focus being on Christ’s suffering and the importance of mainting the Catholic faith.

The power of this bronze lies in the simplicity of its composition. We are immediately transfixed by Christ’s condition, the expression of his suffering by his downturned gaze, without the distraction of the flagellators who might have flanked him. It is a severe rendition of the Catholic, Counter-Reformatory message without superfluousness. Christ’s hair and beard are finely modelled and hand-finished with a hammered surface. The musculature of his lean body is accurately studied and defined. It is a bronze cast of the highest quality, typical of the facture of similar bronzes emerging from the foundries of Paris in circa 1700. During this period in France artists were more frequently working to international but also state-imposed artistic conventions, resulting in a high degree of homogeneity in the finished products.,

The attribution to Corneille van Clève has arisen in comparison to his Leda and the Swan, now in The Louvre, which bears striking similarities to the present bronze Christ. The similarity in the treatment and finishing of the hair, eyelids, lips and drapery is marked, particularly the facture as both are raised on similar square-section bases. The positioning of both figures as they seemingly pace forward, one leg bent and foot raised in contrapposto furthers this point. The slender, athletic forms differ from the more squat examples of Duquesnoy and Girardon’s figures. Therefore, whilst the attribution to Van Clève is not altogether certain, the degree of homogeneity between the present example and Leda and the Swan is significant.

Date: c.1700

Medium: Bronze

Dimension: 42 x 13 x 12 cm (16¹/₂ x 5¹/₈ x 4³/₄ inches)

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie