Shamanism forms the heart of the Anamistic World. The key figure across the Arctic world in mediating between species : Man and Prey and between the spiritual and the physical world, was the shaman, or angekkok. He or she is pivotal figure essential to the inter-relationships between different life forms, able to travel between the natural and supernatural realms. To communicate with the spirit world, shamans used a special magical language. People, animals and hunting implements could not be referred to by their usual names, so for example the walrus, usually aaviq, became sitdlalik in incantations. Perhaps the most vital aspect of the shamans' role was their relationship with Sedna. Sedna the great undersea goddess who must have her hair combed by shaman’s in order for her to release the bounty of the seas which feed the Eskimo.

« A girl lived alone with her widowed father. Cunningly, she was seduced by and married a shaman (or according to other versions, with a fulmar, a man-bird or with a dog). After a while on his distant island, his father heard complaints beyond the sea: it was his daughter who was being mistreated. He boarded his kayak to fetch her and paddled back towards their island. Seeing Sedna run away, her husband with his supernatural powers ordered the sea to break loose. Seeing death approching, the father sacrificed Sedna by throwing her to the sea, but clinging to the edge she put the kayak in danger. The father then cut off his daughter's fingers, which became fish, her thumbs and hands, became seals, whales and all the marine animals. Sedna sank to the bottom of the sea where she still resides as a goddess. When the hunt is not good or the sea is rough, the belief is that Sedna is angry because her hair is tangled and, having no hands, she can not comb it. It is then that the shamans, through their magic, descend into the depths and comb Sedna’s hair and thus restore calm to the ocean and its creatures. This legend causes the male eskimo to treat the sea and women with respect. »

To the Inuit, if rituals were not correctly observed, or taboos were broken, Sedna would become too depressed to comb her hair. Sea mammals would become tangled in it and would not come to the surface to be hunted. Given such potentially catastrophic responses from animals, relationships with sea-creatures needed careful attention. As one Inuit elder describes, 'shamans must swim down to the depths of the sea and comb Sedna’s hair for her. And in her gratitude, she offers humankind all the creatures of the sea. As a further example of how intimate the relationship could be between the Eskimo and their prey there is the story told that describes a walrus being dismayed at a Greenlandic family concealing a miscarriage, reacted in dramatic style, grasping a man 'with his huge fore-flippers, just as a mother picks up her little child', and dragging him into the sea and trying to pierce him with his tusks before finally letting him go.

The shaman was the intermediary between the goddess and mortals, transmitting her wishes and conveying human prayers. In the Arctic, shamanism focused on the quality known in as qaumaniq, generally translated as 'vision', an experience in which the shaman was able to recruit the assistance of tuurngait, the helping spirits. The visionary powers aided the angekkok in a range of social functions : teaching, healing, exposing members of the community who broke taboos and directing hunters to their prey. Shamans could be either men or women and initiation followed lengthy training, often after a kind of apprenticeship to an existing angekkok.

To return to the walrus – Human link it is in the task of visiting Sedna that a particular connection between shamans and walruses emerges. Many shamans were reportedly able to transform themselves into walruses in order to undertake the difficult journey to the Sea Goddess's home at the bottom of the sea. Frequently, the guardian spirits of an angekkok would include a walrus, or at least a being with the head of a walrus. Walruses were also central in the elevation of an angekkok from a lower to a higher grade of practitioner. In some parts of the Arctic, shamans were divided into those called an ekungassok : those skilful but lacking in strength, and those known as a poolik : who were consummate masters of their art. The promotion in status from ekungassok to poolik hinged to a large extent on the shaman's relationship with bears and walruses.

Henry Rink, who published a volume of Tales and Traditions of the Eskimo in 1875, reports that it was 'by being able to invoke or conjure a bear and a walrus' that a shaman became a poolik. After the bear has been conjured it seizes the shaman and 'throws him into the sea', whereupon 'the walrus, devouring them both, afterwards throws up the shamans bones on the beach, from which he comes to life again', transformed to the higher shamanic potency.

Shamanic traditions had resonance well beyond the Arctic. Norse mythology features numerous shape-shifting mages, and there is even a walrus transformation. In the fifteenth-century Saga of Hjalmper and Diver, an evil king pursues the heroes in the form of a walrus 'angry and frightful to behold'. The walrus king is defeated and killed by a warrior in the form of a swordfish and his own daughter in the form of a porpoise.

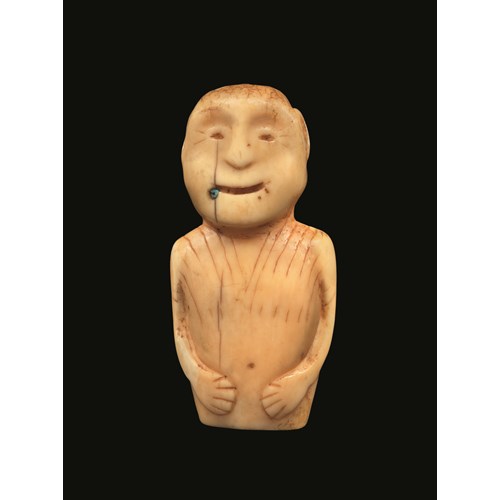

Provenance: Charles Heape, UK prior to Jan. 30, 1897

W.D. Webster, Bicester, UK. Stock number 63, acquired Jan. 30, 1897, from Charles Heape for the price of 1£/1s. and sold to General Pitt Rivers on February 11, 1897 for 2£/10s.

Augustus H. Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, Farnam, Dorset, acquired from Webster February 11, 1897, N° P.1424. He records having paid 2£/7s/6p.

Pitt Rivers Museum, Farnham, Dorset as of January 1, 1898, Room, case 02.

Christie's, London - Tribal Art, 4 Dec. 1990, Lot 186.

Eugene Manning, New York

Charles Heape (1848–1926), a British landowner and businessman from Rochdale, spent his early years with his family in Australia, coming back to Britain after his father died in 1858. Later in life, he recalled stopping in Adelaide where his uncle met some Aboriginal people and bought weapons from them. He later bought objects from many collectors and markets in Britain. Educated in Manchester he later became partner in the firm Strines Calico Printing Company in Rochdale. Heape was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, the RAI and other learned societies. He worked with James Edge-Partington on publishing the famous An Album of the Weapons, Tools, Ornaments, Articles of Dress of the Natives of the Pacific Islands. First [– Second; – Third] series. Manchester: privately published, 1890, 1895, 1898. Heape published articles as well in the 'Transactions of the Rochdale Literary and Scientific Society'. One of his lifelong interests was amassing a complete representative collection of Pacific weaponry. He later donated his entire ethnographic collection of over one thousand objects to the University of Manchester in 1922 some of which are published in the albums he had co-authored Edge-Partington (see above).

William Downing Webster (1868 –1913) began dealing in and collecting ethnographic antiquities in the 1890s. He formed a partnership with his brother Robert Burrow Webster and carried on business as W.D. Webster, Ethnographic Traders. The business published a series of catalogues detailing items available for sale during the next two decades. A number of the catalogues had sketches and photographs representing the works he was trading. He also staged a number of exhibitions of ethnographic material at Earl's Court. In 1899 he travelled throughout Britain purchasing material from British soldiers returning from the Benin Expedition, amassing a large quantity of material that was carefully recorded in his catalogues. He kept good business records recording his correspondence and stock movements. On 31 December 1900 the business partnership with his brother was dissolved and he continued the business under the same name and on his own account. In 1904 he sold the entirety of his collection in a five-day auction in London.

Literature: Illustrated :

Pitt-Rivers, Augustus H. Lane Fox : inventory ledger book, top of p.1424, two watercolor views. Cambridge University Library and Rethinking Pitt-Rivers analysing the activities of a nineteenth-century collector.

and

W.D. Webster : Stock book: Collection number range 1 to 9834 : https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/253553

Plus d'œuvres d'art de la Galerie