Marketplace

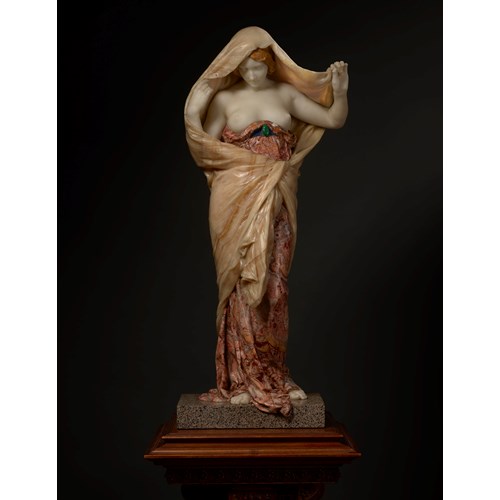

Head of a Philosopher

Pietro Della Vecchia

Head of a Philosopher

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimension 148 x 148 cm (58¹/₄ x 58¹/₄ inches)

Pietro della Vecchia, formerly incorrectly called Pietro Muttoni, was the leading painter in Venice in

the first half of the 17th century, as well as a founding member of the Collegio de Pittori, the precursor

to the great Venetian academy created in 1752. His unique style, tendency towards esoteric subject

matter, and taste for feats of artistic virtuosity made della Vecchia's work highly sought-after by the

most sophisticated Venetian collectors of his day.

Della Vecchia trained under Alessandro Varotari (1588-1648), known as Padovanino, the leading

painter of the first half of the seventeenth century in Venice, and his style attempted to recapture the

classicism of Titian's early manner. His art blends the monumentality achieved by Titian and Tintoretto

with the dramatic chiaroscuro of the Caravaggisti – indeed, Vecchio was married to Clorinda Regnier

(?-c. 1715) the daughter of the accomplished Caravaggesque painter Nicholas Regnier and a talented

artist who imitated both her husband's and her father's style. His first documented work dates to the late

1620s, and by the 1630s Vecchia had become the preeminent religious painter in the city. Well versed

in the art of his 16th-century Venetian predecessors, della Vecchia was also a respected connoisseur,

agent, and restorer, who himself conserved Giorgione's Castelfranco altarpiece in 1643-45. He was a

versatile painter who worked in many genres and created altarpieces, portraits, genre scenes and

grotesques. He also created pastiches of the work of leading Italian painters of the 16th century. Della

Vecchia's affection for and knowledge of Venetian 16th painting, likely nurtured during his time in the

workshop of Padovanino, is evident not only in his original paintings and his restorations, but also in his

capricious imitations of old masters, especially of Giorgione and Titian. These were not simply copies but rather feats of virtuosity designed to appeal to sophisticated connoisseurs. His friend Marco Boschini

recounts a humorous anecdote that when the art dealer Francesca Fontana was assembling a collection

for Cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici he was given a 'Giorgione self-portrait'. This portrait was actually an

imitation by della Vecchia painted from his own features. When the deceit was discovered, della

Vecchia claimed he was solely trying to emulate Giorgione and that he had produced the work 30 years

earlier for his father-in-law Nicolas Regnier. Nicolas Regnier, who was not only a painter but also an

art dealer, had sold the painting. Thirty years later, it was believed that the work was in fact a genuine

Giorgione.

In relation to our painting, it is interesting to consider Titian’s 1546-47 Self-Portrait, in the

Gem.ldegalerie, Berlin and Pietro della Vecchia’s Imaginary Self-Portrait of Titian, probably 1650s,

which was once thought to be by Titian, in the National Gallery of Art, Washington. In these portraits,

Titian is depicted wearing a small skull cap, either for aesthetic reasons or for more symbolic allusions

to various scholars and humanists who had worn similar.

Titian’s Self-portrait would have been admired by many artists working in Venice at the time, including

Agostino Carracci (Bologna 1557 - 1602 Parma). Agostino captured the luxurious textures and produced an engraving, showing a cropped head and shoulders view of the great artist turned to the left,

that came to be one of his most famous prints, admired for the extraordinary talent with which he

rendered the silk vest and fur coat, but above all the intense emotional expression of the artist’s face. This image of Titian was of influence on later generations of painters in Venice, as seen into

the 18th century with portraits such as Titian (c. 1487/90-1576) c.1730-50 by Venetian artist Giuseppe

Nogari (Venice 1699 - Venice 1763). This is one of a series of six identically sized portraits of

famous artists, executed by Nogari in the early eighteenth century. The series was acquired by George

III in 1762 as part of the collection of Joseph Smith, British Consul in Venice, a distinguished collector

and connoisseur as well as a patron of contemporary artists, in particular of Canaletto. Collecting images

of famous artists had become commonplace by the early eighteenth century and artists' portraits

appeared in many of the greatest art collections in Europe.

It is interesting to view our painting, with the skull cap, tilted up-turned head and expressive eyes, as at

least partly an homage to the great master Titian, with whom Pietro della Vecchia had such an affinity,

particularly in its monumentality. However, it also relates to another genre of works for which he is

known, his imaginary portraits of philosophers and bravos which depended to some extent on the

seventeenth-century taste for bizarre subject matter and expressive character heads, or tronies, deriving

from Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Some of della Vecchia’s most popular compositions show astronomers and mathematicians or natural philosophers with their students. The sophisticated taste to

which della Vecchia catered in his imitations of master artists must also have provided the audience for the

artist’s many depictions of arcane subject matter, featuring philosophers and mathematicians, and it is not

improbable that this audience would have recognised subtle, and even somewhat humorous,

references. These portraits are an expression of both the Venetian Baroque's taste for eccentric subject

matter and his involvement with scientific, literary, and artistic academies in Venice which is well documented.

the first half of the 17th century, as well as a founding member of the Collegio de Pittori, the precursor

to the great Venetian academy created in 1752. His unique style, tendency towards esoteric subject

matter, and taste for feats of artistic virtuosity made della Vecchia's work highly sought-after by the

most sophisticated Venetian collectors of his day.

Della Vecchia trained under Alessandro Varotari (1588-1648), known as Padovanino, the leading

painter of the first half of the seventeenth century in Venice, and his style attempted to recapture the

classicism of Titian's early manner. His art blends the monumentality achieved by Titian and Tintoretto

with the dramatic chiaroscuro of the Caravaggisti – indeed, Vecchio was married to Clorinda Regnier

(?-c. 1715) the daughter of the accomplished Caravaggesque painter Nicholas Regnier and a talented

artist who imitated both her husband's and her father's style. His first documented work dates to the late

1620s, and by the 1630s Vecchia had become the preeminent religious painter in the city. Well versed

in the art of his 16th-century Venetian predecessors, della Vecchia was also a respected connoisseur,

agent, and restorer, who himself conserved Giorgione's Castelfranco altarpiece in 1643-45. He was a

versatile painter who worked in many genres and created altarpieces, portraits, genre scenes and

grotesques. He also created pastiches of the work of leading Italian painters of the 16th century. Della

Vecchia's affection for and knowledge of Venetian 16th painting, likely nurtured during his time in the

workshop of Padovanino, is evident not only in his original paintings and his restorations, but also in his

capricious imitations of old masters, especially of Giorgione and Titian. These were not simply copies but rather feats of virtuosity designed to appeal to sophisticated connoisseurs. His friend Marco Boschini

recounts a humorous anecdote that when the art dealer Francesca Fontana was assembling a collection

for Cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici he was given a 'Giorgione self-portrait'. This portrait was actually an

imitation by della Vecchia painted from his own features. When the deceit was discovered, della

Vecchia claimed he was solely trying to emulate Giorgione and that he had produced the work 30 years

earlier for his father-in-law Nicolas Regnier. Nicolas Regnier, who was not only a painter but also an

art dealer, had sold the painting. Thirty years later, it was believed that the work was in fact a genuine

Giorgione.

In relation to our painting, it is interesting to consider Titian’s 1546-47 Self-Portrait, in the

Gem.ldegalerie, Berlin and Pietro della Vecchia’s Imaginary Self-Portrait of Titian, probably 1650s,

which was once thought to be by Titian, in the National Gallery of Art, Washington. In these portraits,

Titian is depicted wearing a small skull cap, either for aesthetic reasons or for more symbolic allusions

to various scholars and humanists who had worn similar.

Titian’s Self-portrait would have been admired by many artists working in Venice at the time, including

Agostino Carracci (Bologna 1557 - 1602 Parma). Agostino captured the luxurious textures and produced an engraving, showing a cropped head and shoulders view of the great artist turned to the left,

that came to be one of his most famous prints, admired for the extraordinary talent with which he

rendered the silk vest and fur coat, but above all the intense emotional expression of the artist’s face. This image of Titian was of influence on later generations of painters in Venice, as seen into

the 18th century with portraits such as Titian (c. 1487/90-1576) c.1730-50 by Venetian artist Giuseppe

Nogari (Venice 1699 - Venice 1763). This is one of a series of six identically sized portraits of

famous artists, executed by Nogari in the early eighteenth century. The series was acquired by George

III in 1762 as part of the collection of Joseph Smith, British Consul in Venice, a distinguished collector

and connoisseur as well as a patron of contemporary artists, in particular of Canaletto. Collecting images

of famous artists had become commonplace by the early eighteenth century and artists' portraits

appeared in many of the greatest art collections in Europe.

It is interesting to view our painting, with the skull cap, tilted up-turned head and expressive eyes, as at

least partly an homage to the great master Titian, with whom Pietro della Vecchia had such an affinity,

particularly in its monumentality. However, it also relates to another genre of works for which he is

known, his imaginary portraits of philosophers and bravos which depended to some extent on the

seventeenth-century taste for bizarre subject matter and expressive character heads, or tronies, deriving

from Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Some of della Vecchia’s most popular compositions show astronomers and mathematicians or natural philosophers with their students. The sophisticated taste to

which della Vecchia catered in his imitations of master artists must also have provided the audience for the

artist’s many depictions of arcane subject matter, featuring philosophers and mathematicians, and it is not

improbable that this audience would have recognised subtle, and even somewhat humorous,

references. These portraits are an expression of both the Venetian Baroque's taste for eccentric subject

matter and his involvement with scientific, literary, and artistic academies in Venice which is well documented.

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimension: 148 x 148 cm (58¹/₄ x 58¹/₄ inches)

Provenance: Anonymous sale, Christie's New York, 23 May 1997, lot 21, where purchased by Rob Smeets

Old Master Paintings;

Purchased from the above at TEFAF Maastricht in 2005 by the Daniel Katz Gallery;

Purchased from the above by a private collector, UK and USA in 2009 from whom purchased

in 2023.

More artworks from the Gallery