Marketplace

Unusual Ghubar Script Qajar Qur'ān

This quarto-format manuscript made of oriental paper contains 28 folios plus 1 flyleaf. The text is inscribed within a frame of 20.3-6 cm high and 11.4-6 cm wide, except for the initial double page described below. The text is copied in ghubar style (alif is around 2 mm high) with 46 lines per page within a frame in blue, gold, red, and green. The initial prayers and sūrah headings are done in blue or red Riqā‘ over gold. The verses are separated by golden rosettes. In the margins, illuminated medallions indicate the juz' and their halves in red ink, the hizb and sajda in blue ink. Each double-page corresponds to one juz’. At the end of the manuscript, the colophon states that the text was copied on 10 Safar 1277 AH / 28 August 1860 AD by Nūr ad-Dīn al-Hassani, son of the late Shihāb ad-Dīn Ahmad.

The manuscript opens with a lavish double illuminated frontispiece, painted largely in gold with polychrome embellishment. The framing on three sides consists of wide bands starting from the top edge of the page, featuring a succession of golden cartouches with floral designs. One of the cartouches contains eight-pointed stars in which the titles of the 114 sūrahs are inscribed in red ink on a gold background. The central rectangle is divided into five parts: on the top, a square with floral decoration includes a large eight-pointed star containing prayers. Below, a purely ornamental frontispiece surmounts a band in which a cartouche indicates the titles of the sūrahs, the number of verses, and the place of revelation in blue ink on a gold background. The next part includes the text, written in a small square within a large frame with floral decoration. In the lower part of the central rectangle, another cartouche contains the verses 77-78 (f. 2r) and 79-80 (f. 1v) of sūrat Al-Wāqi‘a. Margins are filled with a Persian commentary in clouds, written in black and red nasta’liq.

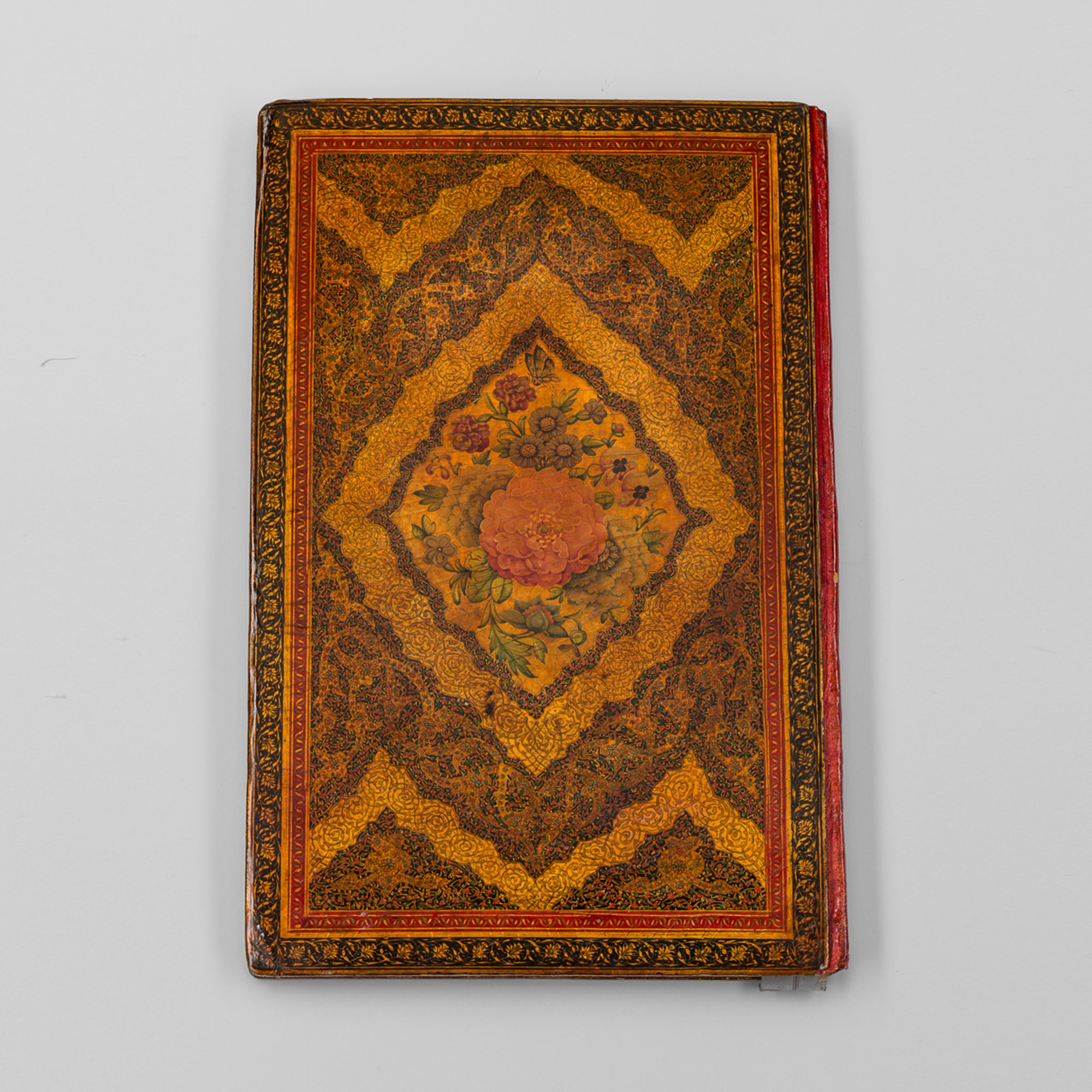

There are three textual lacunae: the first from sūrat Al-Nisā’, verse 76 to sūrat Al-Mā’ida, verse 8 (one folio); the second from sūrat Al-Aʿrāf, verse 119 to sūrat Hud verse 24 (three folios); and the third from sūrat Al-Ahqāf, verse 29 to sūrat At-Tūr, verse 44 (three folios). Originally, the complete manuscript must have comprised 36 folios. We therefore assume that it was later rebound in its original lacquer binding. Its covers are indeed decorated with fine interlacing patterns that recall the motifs of the double frontispiece and a floral design in the center. On the recto of folio 1, there is an owner’s ex-libris stamp slightly blurred, and a later note in Persian dated 1334 AH/1915 AD, written by Ismaʿil Momtaz Dawlah (d. 1933). The latter states that he sent this Qur’ān to his sister, Rutab Khanom, via his brother Ibrahim, as a souvenir of Tehran.

This manuscript is remarkable for the use of ghubar script combined with a quarto-format which, consequently, reduces considerably the number of folios for copying the whole Qur’ānic text. To save space, the copyist incorporated into the double frontispiece the prayers and the index of the sūrahs, that are usually placed before the Qur’ānic text in Qajar copies.

According to some medieval chroniclers, ghubar script is born at the same time as the Six Pens — canonized by Yaʿqūt al-Mustaʿsimi (d. 697 or 698/1297-9) — whose tradition emerged in Baghdad in the 13th century. Probably invented to write messages carried by carrier pigeon, it was then used for amulets, talismans, and even copies of the Qur’ān. One early example – divided into thirty volumes of 4 x 4 cm – that might date back to the 13th or 14th century survived today, preserved in the library of Tehran.

Copying the Qur’ān in a reduced number of pages seems to have been a recognized achievement. The 19th century chronicler Haftqalami reports that a great Iranian calligrapher, ʿAbd al-Baqi Haddad, presented a complete copy of the Qur’ān to Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658 – 1707) containing only 30 folios. This feat earned him the name Yaʿqūt Raqam— Yaʿqūt the scribe. Such a tradition of copying the Qur’ān in a reduced number of pages has continued in later times. Beside the present example, there is another Qur’ān copy with the same layout in the collection of the Islamic Arts Museum in Malaysia (accession no. 2012.11.23). The originality and rarity of these copies perhaps justifies the subsequent journey of the manuscript presented here. At the beginning of the 20th century, it became the property of Ismaʿil Momtaz Dawlah, a powerful Iranian statesman, who sent it to his sister, as a souvenir of Tehran.

The manuscript opens with a lavish double illuminated frontispiece, painted largely in gold with polychrome embellishment. The framing on three sides consists of wide bands starting from the top edge of the page, featuring a succession of golden cartouches with floral designs. One of the cartouches contains eight-pointed stars in which the titles of the 114 sūrahs are inscribed in red ink on a gold background. The central rectangle is divided into five parts: on the top, a square with floral decoration includes a large eight-pointed star containing prayers. Below, a purely ornamental frontispiece surmounts a band in which a cartouche indicates the titles of the sūrahs, the number of verses, and the place of revelation in blue ink on a gold background. The next part includes the text, written in a small square within a large frame with floral decoration. In the lower part of the central rectangle, another cartouche contains the verses 77-78 (f. 2r) and 79-80 (f. 1v) of sūrat Al-Wāqi‘a. Margins are filled with a Persian commentary in clouds, written in black and red nasta’liq.

There are three textual lacunae: the first from sūrat Al-Nisā’, verse 76 to sūrat Al-Mā’ida, verse 8 (one folio); the second from sūrat Al-Aʿrāf, verse 119 to sūrat Hud verse 24 (three folios); and the third from sūrat Al-Ahqāf, verse 29 to sūrat At-Tūr, verse 44 (three folios). Originally, the complete manuscript must have comprised 36 folios. We therefore assume that it was later rebound in its original lacquer binding. Its covers are indeed decorated with fine interlacing patterns that recall the motifs of the double frontispiece and a floral design in the center. On the recto of folio 1, there is an owner’s ex-libris stamp slightly blurred, and a later note in Persian dated 1334 AH/1915 AD, written by Ismaʿil Momtaz Dawlah (d. 1933). The latter states that he sent this Qur’ān to his sister, Rutab Khanom, via his brother Ibrahim, as a souvenir of Tehran.

This manuscript is remarkable for the use of ghubar script combined with a quarto-format which, consequently, reduces considerably the number of folios for copying the whole Qur’ānic text. To save space, the copyist incorporated into the double frontispiece the prayers and the index of the sūrahs, that are usually placed before the Qur’ānic text in Qajar copies.

According to some medieval chroniclers, ghubar script is born at the same time as the Six Pens — canonized by Yaʿqūt al-Mustaʿsimi (d. 697 or 698/1297-9) — whose tradition emerged in Baghdad in the 13th century. Probably invented to write messages carried by carrier pigeon, it was then used for amulets, talismans, and even copies of the Qur’ān. One early example – divided into thirty volumes of 4 x 4 cm – that might date back to the 13th or 14th century survived today, preserved in the library of Tehran.

Copying the Qur’ān in a reduced number of pages seems to have been a recognized achievement. The 19th century chronicler Haftqalami reports that a great Iranian calligrapher, ʿAbd al-Baqi Haddad, presented a complete copy of the Qur’ān to Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658 – 1707) containing only 30 folios. This feat earned him the name Yaʿqūt Raqam— Yaʿqūt the scribe. Such a tradition of copying the Qur’ān in a reduced number of pages has continued in later times. Beside the present example, there is another Qur’ān copy with the same layout in the collection of the Islamic Arts Museum in Malaysia (accession no. 2012.11.23). The originality and rarity of these copies perhaps justifies the subsequent journey of the manuscript presented here. At the beginning of the 20th century, it became the property of Ismaʿil Momtaz Dawlah, a powerful Iranian statesman, who sent it to his sister, as a souvenir of Tehran.

More artworks from the Gallery

_T638447285695169442.jpg?width=500&height=500&mode=pad&scale=both&qlt=90&format=jpg)